Labour aims for growth but how much and of what type of growth is needed?

Hector McNeill is the leading international developer of the Real Incomes Approach to economics also referred to as RIO-Real Incomes Objective. McNeill considers this to be an extension of constitutional economics as a result of its emphasis on public choice.

I had the opportunity to review the recently published Labour Party Manifesto with Hector McNeill and who, in the light of findings set out in his forthcoming book "The Economic Consequences of The Bank of England: 1975-2025" provides some extended insights on the quality and feasibility of growth proposals in general as well as Labour's plans.

Nevit Turk, Senior Economics Correspondent, Agence Presse Européenne, Paris

|

Hector McNeill is Director of the Real Incomes Objective (RIO) Development Programme at SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab the Innovation Division of the George Boole Foundation Ltd.

A graduate of both Cambridge and Stanford Universities he read agriculture, economics and systems engineering.

He initiated the development of the Real Incomes Approach to economics as a distinct theory and applied approach to economics in 1975 when he realized that Keynesian and monetarism could not tackle inflation or stagflation without imposing significant prejudice on the electorate.

RIO is designed to close the operational gaps in Keynesian and monetarist policies. The RIO alternative is the only current policy proposition able to eliminate inflation.

Hector coordinates the Strategic Decision Analysis Group (SDAG) and is Editor of this year's British Strategic Review. |

|

|

Nevit: I had the opportunity to look at the Labour Part Manifesto and wonder what you make of it?

Hector: It is not particularly objective in the sense of object oriented analysis. There are lists of wish lists of desirable changes across regions and sectors but where they have quantified available funds associated with means of raising them they end up with financial resources that are a long way short of any proposition to improve the state of the economy.

I don't want to isolate Labour on this issue simply because this is a general state of affairs present in the case of all of the political parties and independents preparing for this General Election.

In particular on the issue of growth which features as a common and underlying objective there is no statement on the mechanisms or any quantifications so voters have no idea of the extent of promised change. This applies to all parties but also it represents a significant gap in the Labour manifesto.

Nevit: You referred to object oriented analysis. Could you explain what you mean there?

Hector: Object oriented analysis was developed in the early 1960s to build simulation models and to solve the problem of heterogeneity in nature, human activities and economics. It is used to program determinant cause-and-effect models to identify and compare economic policy options. Starting with a range of properties such as real incomes and applying methods (cause-and-effect algorithms) representing policy actions, one generates changes in the target properties. The important point is that both inputs (policy) and outputs as new property values are quantified so it is possible to evaluate meaningful options for policies.

Nevit: But Labour state that they will subject their plans to the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR).

Hector: I haven't seen the OBR doing this type of analysis or, indeed, get things right much of the time. They have to make heroic assumptions and they use quite old economic models such as Cobb-Douglas which do not account for many of the critical variables. In any case the OBR requires quantified inputs and quantified output assumptions from Labour in order to do their job. Otherwise they end up doing Labour's job for them. Labour has not provided them with anything of this sort at the moment especially on the topic of growth.

Nevit: But growth tends to be based on a range of assumptions. In a recent interview, Rachel Reeves referred to the Blair administration's success in achieving growth as an example.

Hector: The Blair administration achieved an average real growth, that is nominal growth minus inflation, of just less than 2% in a phase when energy and commodity prices had settled down. Today, this is nowhere near enough since given the dire state of the economy we need at least 4% real growth to get out of the policy-reated hole we are in.

Nevit: In your forthcoming book you review the impact of monetary policy decisions on the British economy over the last 50 years between 1975 and 2025. You set out the Real Incomes Approach to achieve real growth and recovery. What are the main impacts of monetary policy decisions and why did you select that period? Also what is the solution to our growth predicament? Sorry,that is three questions.

The Economic Consequences of the Bank of England - 1975-2025

by

Hector McNeill

Expected date of publication: June/July 2024

This book is a revealing account of the impact of monetarism on the British economy over the period 1975 to 2025.

The British economist Hector McNeill, reviews the most significant conclusions arising from some 50 years development work that created the new Real Incomes Approach to economics. This book is a revealing account of the impact of monetarism on the British economy over the period 1975 to 2025.

The British economist Hector McNeill, reviews the most significant conclusions arising from some 50 years development work that created the new Real Incomes Approach to economics.

McNeill shows that some 25 years in the last 50, experienced cost-push inflation due to imported exogenous energy resource price rises associated with the OPEC 1973 price sanctions and the more recent Ukrainian affair.

The other 25 years saw cost-push inflation generalized as a result of anticipatory pricing with companies attempting to maintain their profits to safeguard future activity and employment and to ensure that their cash flow was sufficient to purchase their next period’s inputs experiencing rising prices.

This reality nullifies the Quantity Theory of Money which links inflation to demand-pull. It also nullifies the logic of monetary policy decisions of applying raised interest rates to reduce inflation because raising interest rates simply exacerbates the cost-push nature of inflation.

McNeill explains the practical mechanisms giving rise to the deindustrialization of the UK economy such as falling investment and inadequate rises in productivity, falling growth and real incomes, rising income disparity and poverty and the second most negative balance of payments in goods on the planet.

In examining Irving Fisher’s 1911 Quantity Theory of Money and the “cash balance” Cambridge Equation produced by Alfred Marshall, Arthur Pigou and John Maynard Keynes, McNeill points out that these identities are not determinant functions because several important variables are missing including the main asset classes, savings and overseas monetary flow balance. McNeill substitutes these identities with a Real Theory of Money which includes the missing variables. Through this identity he shows how assets such as land and properties respond rapidly to rises in money volumes creating a cost-push impact on goods and service companies and rise in cost of living for households. The resulting diminishing real incomes results in lower savings used for investment loan settlements resulting in declining investment. At the same time, the overseas monetary flow balance for a considerable period between 1975 through 2024 saw a significant rise in offshore investment and globalization. This resulted in a declining national industrial and manufacturing base and falling competitivity and the inevitable growing negative balance of payments for goods.

The essential cause of the current plight of the British economy is shown to be a major innovation and productivity deficit.

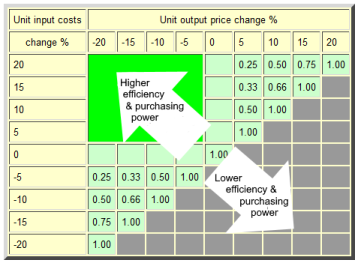

An exploration of the nature of financialization in converting sometimes high physical productivity into one associated with declining national real incomes highlights an indicator which explains the degree to which companies contribute to or reduce inflation. This measure, first used by McNeill in 1975, is the price performance ratio (PPR). This measures the response of company unit output prices to changes in aggregate unit costs.

This associates anticipatory pricing with PPR values equal to or greater than unity (=1.00 or >1.00). Today anticipatory pricing is referred to as “seller’s inflation” or even “greedflation”. On the other hand, a PPR of less than unity (<1.00) is associated with falling inflation and rising consumer purchasing power or real incomes.

Based on this simple finding McNeill’s Real Incomes Approach is supported by a macroeconomic policy proposition, a “Price Performance Fiscal Policy” (3P) which provides incentives for companies to lower inflation by making corporate taxation a function of a company’s PPR. Therefore, to the degree a company reduces inflation its tax obligations fall, even to zero. The national economic benefit is the dissemination of lower priced goods and services distributing real growth throughout the economy as a result of a general rise in the purchasing power and real incomes of the population both as workers and consumers.

Thus, the name of this approach being the Real Incomes Approach.

The essential ingredient to this policy is that companies who volunteer to operate within this fiscal framework can only do so by sustaining a rise in innovation and productivity because the tax rebates can only be received against actual price performance as opposed to “proposed performance”. McNeill provides business rules that can ensure companies optimize their price-setting against feasible unit cost reductions. This is a marked difference to the so-called “Supply Side Economics” marginal tax decreases operated in the 1980s which in the UK resulted in a steep rise in income disparity and with the inappropriate application of interest rates to a massive cost-push inflation seeing over 500,000 households losing their homes due to repossession.

Unlike any contending macroeconomic policy, the Real Incomes Approach’s 3P is able to combine short term price reductions or falling rate of inflation according to the technologies deployed and a sustained advance in innovation and productivity of more-for-less, essential realities for real national growth, actions to address climate change and managing environmental/ecosystem carrying capacity.

|

Hector: That's OK.

Well, varying the order of answers, the period was chosen because monetarism became a dominant component of macroeconomic management in 1975 when Denis Healey the Labour Chancellor panicked as a result of stagflation arising from the 1973 OPEC sanction of raising petroleum prices. (This was..) in response to the "West's" support for Israel. The Treasury did not help matters because they had over-estimated the borrowing requirement. An unnecessary loan was raised with the IMF under imposed austerity conditions.

All subsequent governments, Conservative, Labour and a coalition, applied monetarism with some enthusiasm resulting in deindustrialization of the country, failing investment and inadequate rises in productivity, declining growth and real incomes, rising income disparity and poverty, and to top this off, we arrive in 2024 and Brexit with the second most negative balance of payments for goods on the planet. The reasons for each of these issues is the result of a series of distinct mechanisms all traceable back to monetary policy decisions.

The Real Incomes Approach or RIO-Real Incomes Objective is what it says on the label. All aspects of GDP are measured in terms of real incomes of work forces, companies, profits and consumers across the range and states of conditions of all of these groupings. It should be obvious that applying a top down single-valued interest rates or even income distributive tax rates for individuals and fixed tax rates for companies and then to use personal taxation changes to vary aggregate demand as a device to control inflation, creates chaos. This behaviour is completely illogical. It impacts a very heterogeneous set of individuals and companies with different economic circumstances in a differential fashion creating winners, losers and some who somehow survive in a neutral policy impact state. This is completely unacceptable. Economic policy should not constrain individuals and it certainly should not cause people to face declining real incomes as a direct result of policy decisions.

Nevit: I don't want to stop you in midstream but, in case I forget to ask, can you provide an example of monetary policy decisions causing people to face declining real incomes?

Hector: The Bank of England for well over a century has never eliminated inflation and has reduced the purchasing power of the pound by over 90%. Indeed, for 25 years in the last 50 inflation was caused by cost-push inflation associated with high imported energy resource prices. However, the Quantity Theory of Money proclaims that inflation in the prices of goods and services is caused by excessive money in the economy so interest rates are raised to reduce inflation. However, raising interest rates increases costs and overall cost-push inflation.

Nicholas Kaldor called attention to this in 1979 calculating that, at that time, a 3% rise in interest rates causes a 2% rise in inflation. The Thatcher government and Milton Friedman, advising that government at the time, ignored this advice and as a result more than 500,000 families lost their homes through repossession as a direct result of an inappropriate monetary policy decision to raise interest rates which decimated the real incomes and purchasing power of the families affected.

Nevit: What about the other 25 years? Did monetary policy work effectively then?

Hector: Not really. It was very obvious during the quantitative easing starting in 2008, initially in a period of relatively stable energy prices, involved influxes of large amounts of money and very low interest rates resulting in land, property and commodity positions to absorb a lot of that money raising those prices substantially. These later, as higher prices and rentals for land, commercial and domestic real estate fed into the production of goods and service costs generating cost push inflation. The natural response of companies is to apply anticipatory pricing to raise prices to protect profits to guarantee future operations and employment and to generate an increased cash flow to be able to purchase the next period's inputs facing rising prices. This disseminates cost-push inflation across the economy.

Nevit: So, how would one get rid of cost-push inflation to obtain growth and how would this be quantified?

Hector: Inflation erodes national income. It is the rate at which a country loses GDP. Each time the Bank of England declares the inflation rate they are (also) stating the rate at which country is losing growth.

In the case of the UK, in round figures, a 1% inflation rate loses around £25 billion each year. A 2% inflation loses £50 billion each year. Just at the moment at 3% we are losing around £75 billion each year and yet Labour and other political parties, are at a loss to know where growth is going to come from.

I have studied inflation now for over 50 years and there is a baseline rate of productivity increase across the economy, including all sectors, of about 2% each year or a gain of around £50 billion. This has been the case for many years. However, this is all lost as a result of the Bank of England setting a 2% inflation rate as their policy target considering this to be a state of price stability.

There are, therefore, two ways to recoup this growth. One is to lower inflation to zero, if possible, and the other is to boost productivity. By doing this it is possible to move from a state of zero sum transactions to one characterized by a positive systemic consistency where transactions exhibit mutually beneficial characteristics.

Nevit: Could you explain what you mean by positive systemic consistency?

Hector: This is the Real Incomes policy objective. There is a generally accepted condition known as Pareto optimality where it is assumed that no one can gain unless another one loses as a generalized zero-sum situation. Under RIO the policy objective is to create an across the economy condition, a systemic or generalized norm, characterized by positive or beneficial outcomes becoming the normal or consistent condition providing mutually beneficial transactions.

So what might that be? This is (the condition) where a company raises its profits and income by increasing the real income of customers by lowering their output prices. Under current monetary and fiscal policies this is very difficult to achieve.

Nevit: That sounds a bit counter-intuitive. How can a company lower its prices, raise its profits and benefit consumers all at the same time?

Hector: Well this is happening all the time without policy assistance in the digital information technology and communications domains linked to logic packing densities, miniaturization and lower energy consumption following Moore's Law. This is what is referred to as capital-embodied productivity where the productivity components are built into the technological objects. We have witnessed the prices of these products decline while profitability of the producers have risen as has their market penetration.

Most technologies do not possess this degree of capital-embodied productivity advance and a poor control of inflation undermines any productivity gains they achieve. For this reason macroeconomic policy needs to address this (inflation) issue. At the same time much of productivity gains enabling lowering of prices comes from capital-disembodied productivity associated with advanced decision analysis techniques such as linear programming, time and motion changes, which make use of existing resources in a more efficient manner. Mixed in with all of this is the learning curve dynamic where individuals accumulate tacit knowledge to become increasingly skilled at carrying out repetitive tasks. All such factors contribute to the lowering of unit costs opening up the possibility of moderating increases or even reducing output prices.

The Price Performance Ratio (PPR)

PPR =dUP/dAUC

Where:

dUP is the percentage change in output prices in response to:

dAUC is the percentage change in aggregate unit costs.

|

|

|

As you say, this is counter-intuitive because we have been conditioned to the current monetary policy decisions based on the Quantity Theory of Money, which is flawed. It does not reflect the reality of cost-push inflation and there are many missing variables that determine prices. Also, the current fiscal regime remains blind to individual and corporate circumstances.

In 1975 to understand anticipatory pricing and the degree to which companies contributed to inflation I developed a measure known as the price performance ratio (PPR) which is the percentage change in output prices in response to a percentage change in aggregate unit input costs. This helps track the impacts on the real incomes of companies and their customers. (See Table 1) So a company with a PPR that exceeds unity, or one, is increasing inflation at a faster rate that input costs and is raising the real value of profits and reducing consumer purchasing power. If the PPR is one, or unity, the company is raising unit prices at the same rate as input costs, raising the real value of profits and reducing consumer purchasing power. If the PPR is less than one, or unity, a company is reducing unit prices at a slower rate than input inflation and therefore slowing down the decline in relative purchasing power of consumers.

Therefore the policy challenge is to create incentives for companies to maintain their PPR below one, or unity, by relating corporate taxation to the degree to which a company reduces its PPR below unity.

Nevit: It occurs to me that there is something here that reminds me of some of the logic of Supply Side Economics. Does that make any sense?

Hector: If you mean the Supply Side Economics developed by the Canadian economist Robert Mundell, then there are parallels in terms of logic of attempting to generate investment and productivity as a device to lower inflation. In fact it seems he was developing this proposition at the same time I was developing the Real Incomes Approach. I think the fundamental difference is that Mundell's marginal tax rate reductions to encourage investment are based on presumptions as to the motivation of individuals to, given the opportunity, to invest in a company or invest in themselves.

Certainly in both the USA and UK the adoption of this form of supply side economics resulted in a rapid rise in income disparity and less investment than desired. As I will explain, the Real Incomes Approach policies transfer no benefits on the basis of economist's presumptions or business executive promises but only transfers benefits as a result of actual corporate operational pricing performance. It is only on this basis that under a Real Incomes policy a company itself would benefit from a lower tax rate.

I should add that in Britain we also use tax allowances and such initiatives as super-deductions to incentivise investment. These end up as give-aways simply because they are not conditional to any measures of subsequent performance of participating firms and as a result are not as effective as might be assumed.

Nevit: Yes I see the point you are making. Referring back to the dynamic of pricing and profits, and I suppose this involves your explanation of the Real Incomes policy, how can companies who do not have the obvious technology-productivity advantages of information technology, increase their profits by lowering their output inflation rate or by lowering their price?

Hector: Table 1

| PPR values, inflation, profits & consumer purchasing power

|

| PPR | Inflation | Profits | Consumer real income |

| > 1.00 | accelerates | rise | falls

|

| = 1.00 | at input rate | rise | falls

|

| < 1.00 | declines | falls | rise

| Under Price Performance Fiscal Policy

The Real Incomes Approach

| | < 1.00 | declines | rise | rise |

|

|

Rather than apply marginal cost pricing, which makes companies price-takers, it is necessary to provide incentives for companies to become price-setters. This can be achieved through a combination of optimized price-setting and sustaining improvements through innovation and productivity. Thus, by companies investing to reduce their unit costs combined with price reductions, the PPR falls below 1.00 and corporate taxation can be paid according to the degree a company reduces the PPR below one. (see Tabale 2) So the lower the PPR the lower the tax.

Corporate taxation is replaced by a Price Performance Levy.

The benefit of more competitive price-setting is that sales volumes increase as market penetration takes place gaining more market share. This disseminates lower priced products and services throughout the economy and thereby a broadens the front of rising consumer real incomes or purchasing power. At the same time the profits of companies are compensated by tax rebates and higher sales volumes. Lastly, as can be realized consumers are also the workforce, so the pressure on wages would decline because of the benefits of generalized price stability, or falls, automatically raising purchasing power and the real value of wages.

Nevit: That is really interesting. I am still trying to absorb that since it is quite different from policy treatment to date. Why hasn't this been adopted? I understand this policy was first proposed by you in 1976?

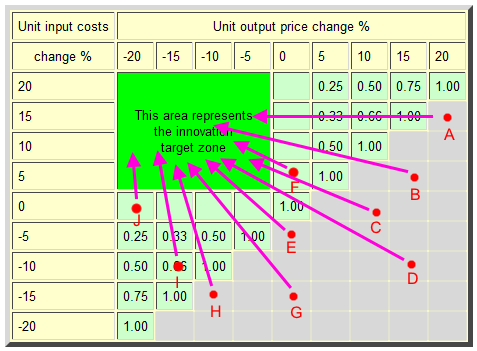

National Innovation Strategy Pathways

Price Performance Fiscal Policy provides a basis for an innovation and productivity strategy on the basis of PPR mapping to indicate in which direction companies will raise income and market penetration and consumers will gain augmented real incomes.

No matter where a goods or service companies are located at any of the points A through J on the PPR map the route to higher returns and rising real national growth is to lower PPRs.

|

|

|

Hector: Yes that is true. The Policy, 3P (Price Performance Fiscal Policy - A Real Incomes Approach), was first set out in 1976 in a monograph published by INTERCOMEX-Intercambio de Mercadorias Ltda (Commodity Exchange) in Rio de Janeiro.

I did a round of the UK political parties in 1981 because of a disastrous budget set out by Geoffrey Howe. However, by that time most economists assisting political parties had become convinced monetarists or remained stubbornly in the Keynesian camp, unable to contemplate another approach.

Two people were particularly supportive at that time. One was Robin Matthews Professor of Economics at Cambridge and at that time Master of Clare College, my alma mater. His feedback helped me transform the policy from an inflation only policy to one able to manage the economy under all conditions. The other person was Richard Wainright the economic spokesman for the Liberal party. His feedback alerted me to the importance of working out how it was to be introduced and administered. Coincidentally it turned out that Wainright had also been a student at Clare College.

Nevit: From the draft of your book that you sent me it is evident that you had concerns about monetary theory as early as 1964 when you were a student. So far we have not discussed your work proposing a different theory of money. What I can't work out is the sequence of events as to whether having identified flaws in the theory you then altered it to then design the Real Incomes Approach. Is that how this happened?

Hector: In reality I completed the policy proposition in 1976. This has essentially remained the same except for changes, for example, in the formulae used to calculate the PPR under inflationary and deflationary conditions. The addition of the deflationary state was based on feedback received from Robin Matthews in 1981.

I only upgraded the Quantity Theory of Money to the Real Theory of Money in 2020, 44 years later. This aspect of my work is still under development.

I received my instruction on policy design as part of my post graduate economics at Cambridge University at the School of Agriculture where policy tended to be based on microeconomic imperatives and an intimate involvement with farm planning across the immense range of farm conditions. I think this is why I developed the basic policy concept reasonably quickly.

The policy work I saw at the Faculty of Economics was more to do with how to apply Keynesian or Monetarist policy instruments. It was simply the management of an already existing framework. I don't recall any instruction to economics students on how to design policies to address specific issues.

However, as you say, I did have issues with the Quantity Theory of Money as a student because simply looking at the identity it is impossible to work out the mechanism as to why companies who are in competition will raise their prices simply because there is more money in the economy. This would be a way to lose market share so there would be no motivation to do as monetarists imagine. Besides lecturers and professors at Cambridge and Stanford not being able to explain why such price rises would occur, I noticed when Milton Friedman was asked the same question he also could only state that this happens in the long run. This, however is not a mechanism. On the other hand, Friedman was right in terms of timing but he, at that time (1975), seemed to be incapable of explaining why this long term effect existed.

Nevit: Just a final point. It looks as if you have identified a way to construct a growth plan while avoiding the issue of having government attempt to choose winners.

Hector: Yes, that is right. Rather than a plan it is a growth strategy where the tactical components consist of the voluntary actions of participating companies who are provided with the opportunity to invest in innovation and productivity in their own fields. This is based on their own decision analysis as to the best options for their profitability and growth. I should add that the business rules under a 3P regime to optimize and maximize growth are slightly different from those applicable under the current monetary and fiscal regimes in force. But these are transparent and make use of well-established methods of planning and implementing productivity enhancing investments.

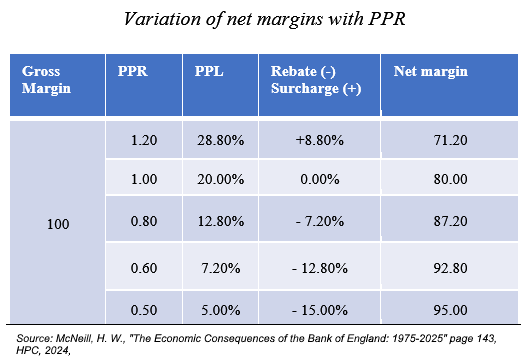

Table 2

Net margins under 3P regime

There are many formulae upon which to base Price Performance Levy (PPL) calculations as a function of a company's Price Performance Ratio (PPR) and a basic tax rate B.

Below is an example of a power function of the form

PPL = B (PPR2)

Where B is a basic tax rate of 20% and PPR is the Price Performance Ratio.

Notice how the net margin increases as the PPR falls in value.

|

|

|

Nevit: Are there any further points that you would like to emphasize concerning Price Performance Fiscal Policy which you have not yet covered and you consider to be worth mentioning?

Hector: I would like to draw your attention to two points.

One is that 3P would reduce the rate of inflation under high inflationary conditions but also under milder inflation it can actually reduce inflation through absolute reductions in output prices creating the same deflationary effect as information technology and communications products. Although many fear deflation, for no particularly logical reason, it is unlikely that most economic activities would be able to maintain a deflationary state of affairs. In any case, the objective would be to attain a zero inflation with a variation of perhaps +/- 0.25% which today would mean a tolerance of a variation in GDP of around =/- $6.25 billion which is (half) the quantity of money the Labour party appear to have identified as potential revenue. However, with 3P lowering inflation by this amount would land the country with a gain of up to $75 billion each year by eliminating the current 3% inflation. This £75 billion would be realized in the form of real growth in real incomes of companies and constituents as members of the workforce and as consumers.

Because of the adaptability of the policy to the specific conditions of companies, it is important to register the fact that the PPR-basis of operation has an important real incomes multiplier effect. So under 3P, in a supply chain with three nodes or operational companies introducing modest PPR values, let us say an average of 0.8, then if the input inflation is 10%, by the time the product leaves the last operator the inflation rate will have been reduced to 5.12% (10& x (0.8)3 = 5.12%). Therefore, in the case of imported inflation, the more operators that exist in the supply line operating within the 3P framework, the more inflation can be reduced.

Under 3P it is more difficult for specific operators to gain a disproportionate share of profits operating within a supply chain because the post-levy margins would adjust to distribute profits in a proportional manner.

Individually, companies can use their additional inputs, designed to lower unit costs, to effect more significant reductions in unit prices.

Policy implementation design would involve establishing the baseline tax rate (B) and then the formula used to increment or reduce the tax levied according to the PPR value.

The reality is that 3P can help companies, at a low risk, to become highly competitive and profitable with the potential of reducing imports through import substitution as well as increasing exports. The fact that the UK is no longer in the European Union makes 3P easier to introduce.

Participation in 3P should be voluntary and probably best to introduce to cover critical supply industries such as utilities and energy.

Lastly, and this will cut through the common political divide in the United Kingdom's discussions concerning private and public operations, involving such questions as the National Health Service where 3P can be applied to public services to improve productivity and to lower costs of operations of the public components a well as maintaining competitive prices amongst suppliers of equipment and other provisions.

Nevit: I have found this to be very interesting and I hope a political party might consider 3P because I think such a practical approach is required given the country's economic circumstances.

Finally I would like to explore the changes you have introduced to monetary theory side in another session if that is agreeable for you.

Hector: That would be fine.

Nevit: Thank you for an interesting exchange.

Hector: Its been a pleasure.

|

|